Farms open their doors to a public interested in learning more about where food comes from and supporting the local agricultural economy

Farmers across Vermont will throw open their barn doors and garden gates to welcome the public for a behind-the-scenes look at Vermont’s vibrant working landscape. Vermont’s first Open Farm Week will be held Monday, August 3 – Sunday, August 9, 2015.

Open Farm Week is a weeklong celebration of Vermont farms. Over 100 farms are participating, many of whom are not usually open to the public. Open Farm Week offers Vermonters and visitors alike educational opportunities to learn more about local food origins, authentic agritourism experiences, and the chance to build relationships with local farmers. Activities vary and may include milking cows and goats, harvesting vegetables, collecting eggs, tasting farm fresh food, scavenger hunts, hayrides, farm dinners, and live music.

Visit DigInVT for a map of participating farms by region. Many events are free and costs vary depending on what activities are offered. Everyone is invited to join the #VTOpenFarm conversations on social media. All participating farms, geographic location, and offerings are at www.DigInVT.com.

Farmers’ markets will also be a part of the Open Farm Week celebration as organizers planned the event to coincide with National Farmers’ Market Week – also the first week of August.

The first Vermont Buy Local Market on the Statehouse Lawn will be held during Open Farm Week on Tuesday, August 4th from 10am-1pm. The Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets is organizing the first Statehouse farmers’ market in collaboration with the Capital City Farmers’ Market and NOFA-VT.

Building off of the success of NOFA-VT’s 2014 Open CSA Farm Day, Open Farm Week is a collaborative statewide agritourism project organized by members of the Vermont Farm to Plate Network including Intervale Center, Vermont Farm Tours, Neighboring Food Co-op Association, Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Vermont Fresh Network, Vermont Department of Tourism, Shelburne Farms and Farm-based Education, NOFA-VT, and City Market. Open Farm Week helps Vermont reach its statewide Farm to Plate food system plan goals to increase farm profitability, local food availability, and consumption of Vermont food products.

Vermont Open Farm Week is made possible by the generous support of Premiere Sponsor: City Market/Onion River Coop as well as the Vermont Department of Tourism and Marketing; Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food and Markets, Localvore Today and Woodchuck Hard Cider.

13 Jul 2015

Making Biofuel

Making biofuel, it sounds like a complicated process taking place in a laboratory somewhere, but in reality it’s quite simple and happening in small, rural Vermont farms. Vermont farmers like John Williamson of State Line Farm and others are electing to create their own fuel and meal. These farmers are enjoying the benefits of the distance to source resiliency and cost reliability that comes with the local production for local use biofuel model they have adopted.

Making biofuel, it sounds like a complicated process taking place in a laboratory somewhere, but in reality it’s quite simple and happening in small, rural Vermont farms. Vermont farmers like John Williamson of State Line Farm and others are electing to create their own fuel and meal. These farmers are enjoying the benefits of the distance to source resiliency and cost reliability that comes with the local production for local use biofuel model they have adopted.

As John Williamson, a Vermont Bioenergy grant recipient says, “100 years ago everyone produced their own fuel; we are just doing that now in a different way.” This is a novel way to look at what he is doing on his North Bennington farm. Vermont farmers in the past would plan to allocate their acreage to feed their livestock, some of which aided in energy-intensive farm activities like plowing, planting, and the eventual harvesting of their field. With the local production for local use model, John is now thinking about how to feed his tractor so he can do the same activities. So what is the feed of choice for John’s John Deer tractor? Sunflowers!

John loads dry and clean sunflower seeds into hoppers on a TabyPressen Oilpress, where screw augers push the seed through a narrow dye. Extracted oil oozes from the side of the barrel and is collected in settling tanks while pelletized meal is pushed through the dye at the front and is stored in one-ton agricultural sacks. The first of the two byproducts, the seed meal, can fuel pellet stoves, serve as fertilizer for crops, or find its way to local Vermont farms to supplement animal nutrition as livestock feed. The second byproduct, the fuel, could at this point be used as culinary oil for cooking, but instead will experience further refinement and become biofuel.

The processing of the oil takes place in Johns self-designed Biobarn. In the below video, John Williamson and Chris Callahan of University of Vermont Extension show us how they can grow oil crops, make biodiesel, feed animals, and save money!

29 Jun 2015

Soybeans for On-farm Biodiesel Production

Mark Mordasky, owner of Rainbow Valley Farm in Orwell, Vermont has been growing soybeans as a cash crop and for on-farm biodiesel and animal feed since 2008. When fuel prices began to climb, Mark took initiative and started searching for an innovative and more cost efficient way to meet his farm’s energy demands. The Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund was able to help Mark take his first steps towards sustainable biofuel production. Mark is able to press these soybeans after harvesting and make two distinct products, oil and meal. The meal is an instantly marketable product and can be sold as feedstock or organic fertilizer; the oil will be further processed into biodiesel.

Soybeans crops are well suited for biodiesel production in Vermont and perform best in heavy soil like those found in Addison County, as University of Vermont Extension Agronomist, Heather Darby explains. Soybeans don’t always do well in in light, well drained soils, and as with any crop the best way to understand the demands of any crops is to contact your University Extension and have your soil tested. Additionally, because soybeans are a legume, they produce nitrogen in association with bacteria, meaning that these crops don’t require the application of additional nitrogen to produce a high yield. These low input, high yield crops are fairly easy to grow, are well suited to the Vermont climate, and afford farmers flexible planting dates. Heather and the rest of the UVM Extension team have seen yields ranging from 35 bushels per acre to up to 85 bushels per acre with varying practices.

In the below video, Mike Mordasky shares his experience and knowledge of soybean production from planting through harvesting harvest and beyond to storage and the creation of the final products. In addition, Heather Darby shares here insights into maturity groupings, variety selection, and best growing practices.

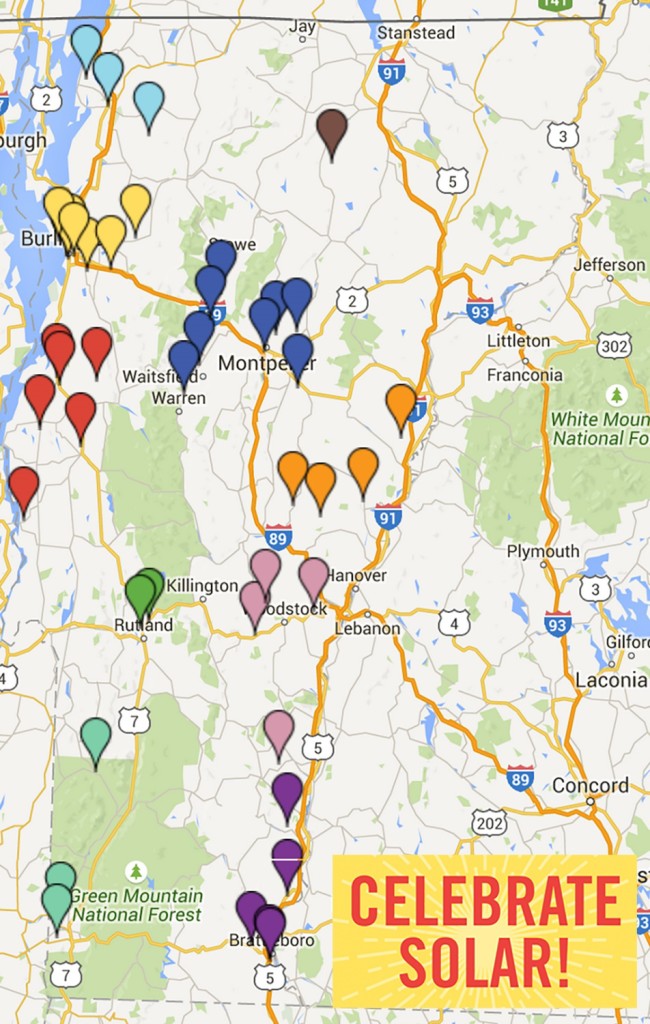

Vermont’s solar industry is lauding Governor Peter Shumlin’s proclamation of the third Saturday in June as “Celebrate Solar Day” in Vermont.

The solar proclamation, announced at the Whitcomb Farm in Essex, coincides with this June 20th, when solar projects in communities throughout Vermont will be open for public tours. June 20 is the weekend of the Summer Solstice.

Like open sugarhouse weekend in the spring and open art studio weekend in the fall, the inaugural summertime tours will give Vermonters the opportunity to get an up-close view of solar systems to learn about the technology, solar economics, and the benefits of solar to our community. Solar customers, host farmers, and owners will be on-hand to speak with the public.

More than 50 systems across all regions of the state will be participating in Celebrate Solar Tours and a map of open tours can be found here. Many participating sites will host refreshments, music, or other entertainment. Other planned solar events include community walking tours of residential solar installations, miniature golf, a self-guided bike tour, and on-site yoga.

The Governor’s proclamation notes that “solar energy represented 99% of new electrical capacity in the state in 2014 and more than 5,000 Vermont customers have installed solar” through Vermont’s net metering program.

Further, it cites that the Vermont clean energy industries employ over 15,000 Vermonters, with solar providing “a broad spectrum of employment opportunities, helping retain and attract Vermonters working in manufacturing, installation, and sales, among other careers.”

The Whitcomb family is host to a 2.2 Megawatt solar farm that provides energy for Vermont’s SPEED program.

Among the solar sites open to tour June 20: iconic and sweet Vermont attractions like Cold Hollow Cider and Morse Farm Maple Sugarworks, high-tech attractions like Draker and Small Dog Electronics, agricultural farms like Champlain Orchards, shared community solar arrays, and some of Vermont’s highest producing solar farms.

At the announcement of the solar tours, Paul Brown, owner of Cold Hollow Cider in Waterbury Center, which has a 150kW system powering its operations, said of the event, “Folks know us and visit us for our cider and donuts. But we are thrilled to open up the field behind our cidery to share the benefits of solar technology to our business and our community. We’ll of course also be serving up some sweet treats for those who come by.”

About Celebrate Solar Tours – June 20

The first annual Celebrate Solar Tours on June 20 will feature public tours of more than 50 solar systems of varying size throughout the state. The public will have the opportunity to get an up-close understanding of the technology, economics and benefits to the community. Open systems will be designated with roadway signage and many will feature music, refreshments or other entertainment.

Contact: Ansley Bloomer

Ansley@revermont.org or 802-595-0723

08 Jun 2015

Grass Energy in Vermont

University of Vermont Extension Agronomist, Sid Bosworth explains in the field his research into use of grasses for combustion and thermal energy

In 2008, the Vermont Bioenergy Initiative began to explore the potential for grasses energy grown in Vermont to meet a portion of the state’s heating demand and reduce the consumption of non-renewable fossil fuels. The Grass Energy in Vermont and the Northeast report was initiated by the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund, and carried out by its program the Vermont Bioenergy Initiative, to aid in strategic planning for future grass energy program directives.

Grass Energy in Vermont and the Northeast summarizes current research on the agronomy and usage potential of grass as a biofuel, and points to next steps for the region to fully commercialize this opportunity. The keys to commercializing grass for energy are improving fuel supply with high-yielding crops, establishing best practices for production and use, developing appropriate, high-efficiency combustion technology, and building markets for grass fuel.

Perennial grasses, while serving as a biomass feedstock for heating fuel, also have numerous other benefits to farmers. The grass energy benefits reviewed in the report include retaining energy dollars in the local community, reducing greenhouse gas emissions from heating systems, improving energy security, providing a use for marginal farmland, and reducing pollution in soil and run-off from farms.

Regional and closed loop processing were two models recommended by the report, both involving farmers growing and harvesting grass, but differing in where the grass is processed into fuel and where it is used. The regional processing model calls for aggregating grass from a 50-mile radius at a central processing facility, where the grass is made into and used as fuel, or sold to local users. The closed loop model suggests farmers growing and processing grass on-site for on-farm or community use. Other models, like mobile on-farm processing and processing fuel for the consumer pellet market have significant hurdles to overcome if they are to be successful in Vermont.

In the below video a Vermont agronomist explains switchgrass production followed by entrepreneurs turning bales of grass into briquette fuel. This grass biofuel feedstock can be grown alongside food production on marginal agricultural lands and abandoned pastures, and in conserved open spaces. The harvested grass can be baled and used as-is in straw bale combustion systems, or it can be compressed into several useable forms for pellet fuel combustion systems.

For more information on grass biofuel feedstocks and to read the full Grass Energy in Vermont and the Northeast report visit the grass energy section of the Vermont Bioenergy website.

01 Jun 2015

Food Versus Fuel – Local Production for Local Use – Biodiesel as Part of Sustainable Agriculture

Nationally, corn-based ethanol and palm oil based biodiesel are gaining negative attention for their impacts on the environment and food security. But here in Vermont, farms are producing on-farm biodiesel to power equipment and operations on the farm and the local farm community. This is a profoundly different model from national and international biofuel production. Agricultural Engineering and Agronomy Researchers at University of Vermont Extension in partnership with farmers and the Vermont Bioenergy Initiative have developed a model of local minded, on-farm production of biofuels that can help rural communities transition away from unsustainable models of food, feed and fuel production.

National and global models of corn-ethanol and soy oil-biodiesel production are resulting in large-scale land conversions in some parts of the world, in particular to a loss of native grass and forestland. This type of biofuel production is not happening in Vermont, where bioenergy production incorporates rotational oilseed crops like sunflowers and soybeans on Vermont farms.

Locally produced biodiesel supports resiliency in Vermont, a cold climate state which is particularly dependent on oil. Over $1 billion leaves the state for heating and transportation fuel costs. Heating and fuel independence by producing on-farm biodiesel provides farmers fuel security which is comparable to that which is sought by Vermont’s local food movement.

The local production for local use model results in two products from one crop: oil and meal (animal feed or fertilizer). By growing oilseed and pressing the seed to extract the oil, farms are creating a valuable livestock feed at home, rather than importing it. The oil can be sold as a food product, used directly in a converted engine or converted to biodiesel for use in a standard diesel engine. In this way, oilseed crops offer flexibility in the end-use of the products. US corn-based ethanol mandates are raising grain costs nationally, making feed expensive for Vermont farmers. Local bioenergy production means farmers produce their own feed, fuel, and fertilizer for on-farm use, at a fraction of the cost and more stable prices. Reduced and stable prices for feed, fuel, and fertilizer can mean improved economic viability for Vermont farms and more stable food prices for Vermont consumers in the future.

Overall viability can be seen in the local production for local use model by considering economics, energy and carbon emissions. Biodiesel production costs of between $0.60 and $2.52 per gallon have been estimated for farm-scale production models, which are generally below market price for diesel fuel. The net energy return in Vermont on-farm biodiesel operations has been estimated at between 2.6 and 5.9 times the invested energy (i.e. more energy out than was required to produce the fuel), demonstrating strong returns and potential for improvement with increased scale. Furthermore, oilseed-based production of biodiesel has been estimated to result in a net reduction of carbon dioxide emissions of up to 1420 lbs. per acre, the equivalent of about 1500 miles of car travel per year.

Categorizing the Vermont biofuel model with national models and trends is inaccurate, considering the innovative and efficient systems benefiting Vermont farmers. While national and international analysis weighs the benefits of food versus fuel, the model is quite unique in Vermont and the food versus fuel challenge is well met. The model developed in Vermont does however have wider-reaching implications in that this can be replicated in rural farm communities across the US.

As John Williamson of Stateline Farm, a Vermont Bioenergy grant recipient says, “100 years ago everyone produced their own fuel; we are just doing that now in a different way.”

In order to meet the goals set by Vermont’s comprehensive energy plan for Vermont to produce 90 percent of the state’s energy needs from renewables by 2050 and reduce Vermont’s greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent from a 1990 baseline, Vermont farmers will have an important role to play. As Vermont experiences growth in food-related businesses and jobs, decisions about energy become more important prompting statewide energy and agriculture collaborations. In the following episodes of Across the Fence, UVM Extension agricultural engineer and Vermont Bioenergy Initiative biofuels consultant, Chris Callahan, shares two stories about Vermont farmers who are rethinking their on-farm energy. In both examples UVM extension is able to work with the farmers to help make cleaner, renewable on-farm energy sources a practical solution that saves money and results in greenhouse gas reductions.

Learn more in a series of on-farm energy case studies produced by Vermont’s Farm to Plate Initiative.

19 May 2015

Mitigating Potential Biomass Feedstock Pests

The Vermont Bioenergy Initiative aims to connect diversified agriculture and local renewable energy production for on-farm and community use by supporting research, technical assistance, and infrastructure development in emerging areas of bioenergy including biodiesel production and distribution. As we move into the growing season, there are a variety of pests that can potentially affect sunflower, canola, and soybean biomass feedstock production. In this video a University of Vermont agronomist explains how to control theses potential biomass feedstock pests and increase crop, and eventually biofuel, yields without heavy reliance on pesticides and herbicides.

- February

- Biomass Boot Camp, February 23, Catonsville, MD

- Farm Energy IQ – Training for NE Ag Service Providers in VT February 23- 25, Fairlee, VT

- ACI’s 4th Carbon Dioxide Utilization Conference 2015 February 25-26 San Antonio, TX

- 2015 Executive Leadership Conference. 25 February – 1 March 2015. Phoenix, Arizona

- March

- World Agri-Tech Investment Summit. March 3-4, 2015 San Francisco, CA

- Waste to Biogas and Clean Fuels Finance and Investment Summit. March 3-4 San Jose, CA

- Farm Energy IQ – Training for NE Ag Service Providers March 10-12, 2015 State College, PA

- Advanced Bioeconomy Leadership Conference March 11-15, 2015 Washington, DC

- Next-Generation Defense Energy Symposium. 17 – 18 March, 2015. Washington, United States

- WEBINAR: Using B100 in Our Class-8 Trucking Operations (60 trucks) in Tennessee March 19, 2015 10:00 AM ET

- ACI’s Annual Lignofuels Americas Summit March 25-26, 2015 Milwaukee, WI

- Forest Products and Timberland Investment Conference. March 31-April 1, 2015. New York, NY

- April

- Applying Renewable Energy – Online Training April 01, 2015 at 09:00 AM to June 30, 2015 at 06:00 PM

- Farm Energy IQ – Training for NE Ag Service Providers in NJ, April 8- 10, Bordentown, NJ

- 5th Defense Renewable Energy Summit. 7-8 April 2015. Arlington, VA

- Good Jobs, Green Jobs 2015 April 13 Washington, D.C

- 2015 Northeast Biomass Heating Expo. April 16-18, 2015. Portland, ME

- Introduction to Renewable Energy Technologies Start date: 20 to 22, 2015

- International Biomass Conference and Expo. 20 -22 April 2015. Minneapolis, MN

- 37th Symposium on Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals. April 27 – 30, 2015 San Diego, CA

19 Sep 2013

State Line Farm

Feedstock: Sunflowers, canola, mustard

Feedstock: Sunflowers, canola, mustard

Fuel: Biodiesel

Energy Output: Power (for farm machinery)

Services: Oilseed and Grain Grower, Oil milling, Fuel Processing, Feed Supply

Owner: John Williamson

Location: Shaftsbury, Vermont; Bennington County

On the forefront of oilseed crop growing in a northeastern climate, State Line Biofuels is Vermont’s first on-farm facility making biodiesel made from oilseed crops grown on-site and from neighboring farms.

The Williamson family has owned State Line Farm in southwest Vermont alongside the border of New York since 1936. For many years, State Line was run as a traditional dairy farm, but falling milk prices caused them to sell the herd and look towards diversifying the farm’s operations.

John and his family currently produce maple syrup, honey, sorghum syrup and hay for sale in local markets. Since 2004, State Line Farm has also experimented with sunflower, canola, mustard, and flax varieties in an effort to fuel their farm with biodiesel.